There is something daring in seeking out an exchange with someone, especially a stranger. For such occasions, cultures around the world develop a repertoire of easy conversation starters. In the United States and Canada, however, one opener dominates: what do you do?

Whatever the reason—the influence of a Protestant work ethic, or a desperate attempt to not appear classist—North Americans habitually start a conversation with strangers by asking what they do for a living. It’s one of many customs in which American cultural norms deviate from those of the UK and Europe.

In most places in the world, asking a stranger what kind of work he or she does, especially without any pretext, is frowned upon. And now, “What do you do?” is finally becoming a tainted question in North America, too.

Learn from the French

In the US, national politics have made people more self-conscious about longstanding class divisions, while the gig economy has made work itself a more complicated concept. The question of what one does, therefore, feels a lot more loaded than it used to.

The disdain for this opening line is nothing new for the French, who have been known for shutting down chats with Americans who ask the dreaded “What do you do?”

In their new book, The Bonjour Effect: The Secret Codes of French Conversation Revealed, authors Julie Barlow and Jean-Benoît Nadeau elaborate on why you should never ask a French person about their work. The reaction is not just about the conversation starter’s affront to egalitarianism (a concept the French value dearly, even if they don’t live it, Barlow says). Rather, the French frequently enjoy pretending that they don’t like their jobs. So, just like money, work is a boring topic.

“They will be offended, believing you’re trying to put them into a box,” Barlow, a French-Canadian, tells Quartz. “And they just don’t think it’s interesting to work for a living. There are other things they’d much rather talk about.”

To the French, she explains, conversations are for exchanging points of view, not finding things in common, the goal of conversation for North Americans.

Counterintuitively, the French do not find it rude or elitist to ask about where a person likes to vacation, but that’s because it’s common for people there to take an average 30 days of paid vacation per year. In any case, it’s a nice alternative to staring blankly into the middle distance for too long the next time you encounter a stranger.

However, the typical French openers that may translate with more ease are things like, “Which part of the country are you from?” (Notably, it’s not “where are you from?” which, in France, could imply you are not French, Barlow explains. That could be a danger in the US, too, where immigration and citizenship have become fiercely debated topics.)

Relatedly, any questions about geography or the food in a person’s hometown or region tend to get people chatting.

Stay within “Tier one”

Food also is on Daniel Post Senning’s list of safe “tier one” topics, meant for encounters with people you don’t know. Post Senning is Emily Post’s great-great grandson, and a co-author of Emily Post’s Etiquette, 18th edition. With other Post descendants, he now works for the Emily Post Institute running seminars on etiquette and communication for businesses and individuals. In his teachings, second-tier topics are religion, politics, dating, and one’s love life. Tier three, for your closest associates, expands to family and finances.

For strangers, tier one is safest. Other options here include sports (including historical, memorable moments), pop culture, and hobbies. “People say hobbies are boring, but what if a person’s hobby is particle physics?” Post Senning argues. “Or painting. The arts are not boring.”

What’s not in tier one? Work.

Try triangulation

If you do have a preoccupation with finding out what someone does (I’ll admit it, I’m always curious), Post Senning says to wait for an opening. A comment about a long day or a demanding boss may make it safe or even polite to probe a little. But pay attention to how people respond and be prepared, with a fresh topic at hand, to back off.

“They may just feel like: Look, it’s all I do 40 hours a week or more, it’s the last thing I want to talk about,” Post Senning says.

As an alternative, one of the easiest routes into a conversation may be to remark on a shared experience—yes, you can have these with a stranger; think of the weather, or the spread on offer at a party. Post Senning suggests an ice breaker like, “Looks like it’s about to rain” or “This food looks delicious.” But these mini-commentaries don’t always have to be that mundane. Your opening line could be an appreciation of the quality of light coming through a window, he suggests.

Kio Stark, author of When Strangers Meet: How People You Don’t Know Can Transform You, refers to the shared-experience strategy as triangulation. “The triangle is made up of you, a stranger, and a third thing that closes the loop—that might be something that you’re both experiencing or seeing that’s worthy of notice,” she told CityLab, explaining:

There might be a cute dog or someone doing something strange—an itinerant preacher on the subway, say. In those situations, you’re more likely to exchange a glance with someone, and that might be the whole outcome, or you could say something like: “Wow, he’s really fire and brimstone today.”

She also likes to notice small things and give people compliments like, “Nice shoes.” People love to fill her in on the details.

Once a conversation has started, if she’s asked about a topic for which she could respond with a full, personal disclosure—beyond the details she’d normally share with a stranger— she may very well go for it. “We tend to meet disclosure with disclosure, even when we talk to strangers,” she says.

For instance, if someone asks about her father, she may choose to mention that he passed away when she was a child. When that happens, she says, she almost invariably is told about a loss the other has experienced. A random encounter can become profound.

Forget yourself

Talking to new people isn’t only a shortcut to learning more about the ways other people live, and perhaps stepping outside your own social echo chambers, it’s also beneficial: Sociologists have found that even weak ties, like those made while chatting with fellow commuters or travelers, are linked to feelings of well-being. And, of course, those weak ties to someone who’s vacationing at the same place as you may organically stretch into a lifelong friendship.

One final tip: If you tend to be neurotic when talking to people, and anxious about what they might think of you, recognize that your concern might paradoxically make you a jerk. Consider what the writer Jennifer Latson learned about herself while doing research for a recent book. As she explained in New York Magazine: “I focus so much on saying exactly the right thing that I hardly pay any attention to the other person. I’m more concerned about how I look to them than I am about getting to know them.”

Most people want to connect, she discovered, and they aren’t judgmental about whether you remember names or little details. You’ll probably be excused even if you accidentally blurt out that suddenly gauche question we’re all trying to avoid—unless, of course, you’re talking to the French.

emotional intelligence tests and training, serving more than 75% of Fortune 500 companies. His bestselling books have been translated into 25 languages and are available in more than 150 countries. Dr. Bradberry has written for, or been covered by, Newsweek, BusinessWeek, Fortune, Forbes, Fast Company, Inc., USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, and The Harvard Business Review.

emotional intelligence tests and training, serving more than 75% of Fortune 500 companies. His bestselling books have been translated into 25 languages and are available in more than 150 countries. Dr. Bradberry has written for, or been covered by, Newsweek, BusinessWeek, Fortune, Forbes, Fast Company, Inc., USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, and The Harvard Business Review.

L’essor démographique et la croissance économique n’ont jamais autant pesé sur les ressources en eau. En se basant sur les pratiques actuelles de consommation, on estime que la planète sera confrontée d’ici 2030 à un déséquilibre de 40 % entre l’offre et la demande mondiale en eau.

L’essor démographique et la croissance économique n’ont jamais autant pesé sur les ressources en eau. En se basant sur les pratiques actuelles de consommation, on estime que la planète sera confrontée d’ici 2030 à un déséquilibre de 40 % entre l’offre et la demande mondiale en eau. besoins en eau pour la production d’énergie sont voués à croître, sachant que 1,3 milliard de personnes sont encore privées d’accès à l’électricité. Enfin, plus de la moitié de la population mondiale vit actuellement en ville et ce processus d’urbanisation s’accentue rapidement. Et comme les nappes phréatiques s’épuisent plus vite qu’elles ne se reconstituent, près de 1,8 milliard de personnes vivront en 2025 dans des régions ou des pays qui connaîtront une pénurie d’eau absolue.

besoins en eau pour la production d’énergie sont voués à croître, sachant que 1,3 milliard de personnes sont encore privées d’accès à l’électricité. Enfin, plus de la moitié de la population mondiale vit actuellement en ville et ce processus d’urbanisation s’accentue rapidement. Et comme les nappes phréatiques s’épuisent plus vite qu’elles ne se reconstituent, près de 1,8 milliard de personnes vivront en 2025 dans des régions ou des pays qui connaîtront une pénurie d’eau absolue. accomplis ces dernières décennies, 2,4 milliards de personnes n’ont toujours pas accès à des installations sanitaires correctes, et un milliard d’entre elles défèquent à l’air libre. Au moins 663 millions de personnes sont en outre toujours dépourvues d’un accès à une eau potable de qualité. Chaque année, près de 675 000 personnes décèdent prématurément en raison d’installations sanitaires insuffisantes, d’une eau insalubre et du manque d’hygiène. Dans certains pays, cette situation se traduit par un manque à gagner annuel qui peut représenter jusqu’à 7 % du produit intérieur brut.

accomplis ces dernières décennies, 2,4 milliards de personnes n’ont toujours pas accès à des installations sanitaires correctes, et un milliard d’entre elles défèquent à l’air libre. Au moins 663 millions de personnes sont en outre toujours dépourvues d’un accès à une eau potable de qualité. Chaque année, près de 675 000 personnes décèdent prématurément en raison d’installations sanitaires insuffisantes, d’une eau insalubre et du manque d’hygiène. Dans certains pays, cette situation se traduit par un manque à gagner annuel qui peut représenter jusqu’à 7 % du produit intérieur brut.

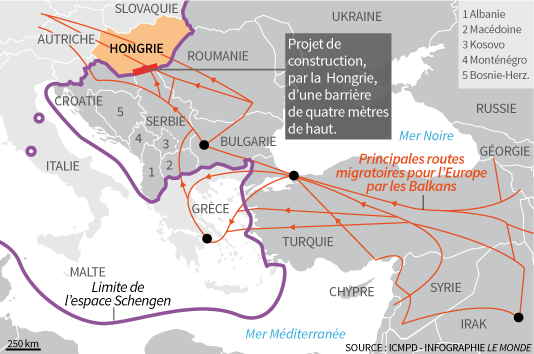

justifiées des ONG européens. Ironie de l’histoire, ce mur se dresse dans le premier pays de l’ancien bloc de l’Est qui avait fait tomber le rideau de fer né de la guerre froide, en mai 1989,qui séparait l’Europe en deux pendant plus de trente ans. Cette clôture « anti-migrants » a été érigée sur une distance de 175 kilomètres, elle est composée de deux palissades métalliques hautes de 4 mètres et espacées de 6 mètres l’une de l’autre, chacune couronnée d’une épaisse couche de barbelés. Cette structure est accompagnée de miradors high-tech avec projecteurs et caméras thermiques pour détecter les mouvements de ceux qui essaieraient de se frayer un chemin pour traverser. Un chemin bitumeux a été aménagé pour permettre aux soldats de patrouiller du coté Hongrois. Cette barricade s’étend aussi sur la frontière de la Croatie et s’étendra bientôt face à la Roumanie. Cette démarche ne grandit pas l’Europe.

justifiées des ONG européens. Ironie de l’histoire, ce mur se dresse dans le premier pays de l’ancien bloc de l’Est qui avait fait tomber le rideau de fer né de la guerre froide, en mai 1989,qui séparait l’Europe en deux pendant plus de trente ans. Cette clôture « anti-migrants » a été érigée sur une distance de 175 kilomètres, elle est composée de deux palissades métalliques hautes de 4 mètres et espacées de 6 mètres l’une de l’autre, chacune couronnée d’une épaisse couche de barbelés. Cette structure est accompagnée de miradors high-tech avec projecteurs et caméras thermiques pour détecter les mouvements de ceux qui essaieraient de se frayer un chemin pour traverser. Un chemin bitumeux a été aménagé pour permettre aux soldats de patrouiller du coté Hongrois. Cette barricade s’étend aussi sur la frontière de la Croatie et s’étendra bientôt face à la Roumanie. Cette démarche ne grandit pas l’Europe. l’espace Schengen – (26 états) à l’intérieur du quel les voyageurs se déplacent sans contrôle – , le gouvernement Hongrois a mis en place une législation, la plus sévère de l’Union Européenne. La simple entrée sur le territoire Hongrois sans autorisation est devenue un crime. Les demandeurs d’asile sont systématiquement placés en centre de détention dans les camps établis le long de la clôture et n’ont pas accès aux journalistes. Ces dispositions sont contraires au

l’espace Schengen – (26 états) à l’intérieur du quel les voyageurs se déplacent sans contrôle – , le gouvernement Hongrois a mis en place une législation, la plus sévère de l’Union Européenne. La simple entrée sur le territoire Hongrois sans autorisation est devenue un crime. Les demandeurs d’asile sont systématiquement placés en centre de détention dans les camps établis le long de la clôture et n’ont pas accès aux journalistes. Ces dispositions sont contraires au  droit européen qui reviennent à emprisonner plusieurs mois ces personnes, au terme du processus, neuf personnes sur dix voient leurs demandes rejetées. La Hongrie crie haut et fort qu’elle applique les conventions internationales et ses obligations légales, mais les sept juges de la cour européenne ne sont pas de cet avis (Arrêt du 28 février 2016) estimant que la Hongrie ne respecte pas ses engagements dans ce domaine.

droit européen qui reviennent à emprisonner plusieurs mois ces personnes, au terme du processus, neuf personnes sur dix voient leurs demandes rejetées. La Hongrie crie haut et fort qu’elle applique les conventions internationales et ses obligations légales, mais les sept juges de la cour européenne ne sont pas de cet avis (Arrêt du 28 février 2016) estimant que la Hongrie ne respecte pas ses engagements dans ce domaine. 363000 personnes ont frappé à la porte de l’Europe contre 1 million l’année d’avant, grâce à l’accord conclu avec la Turquie. La crise est loin d’être terminée et l’Europe ne semble pas être la hauteur de ce défi humanitaire sans précédent depuis la seconde guerre. L’Italie avec 85% (118000) migrants venus de Libye, tandis que 2400 périssaient en mer, loin des Balkans au large des côtes, loin des caméras.

363000 personnes ont frappé à la porte de l’Europe contre 1 million l’année d’avant, grâce à l’accord conclu avec la Turquie. La crise est loin d’être terminée et l’Europe ne semble pas être la hauteur de ce défi humanitaire sans précédent depuis la seconde guerre. L’Italie avec 85% (118000) migrants venus de Libye, tandis que 2400 périssaient en mer, loin des Balkans au large des côtes, loin des caméras. Libye pour éviter que les personnes prennent des risques fous alors qu’ils ne sont pas éligibles à l’asile. Pour y arriver, il faudra que le calme s’installe dans ce pays l’autre voie pour les africains de l’ouest est la route du Maroc avec des centres d’enregistrement délocalisés situés en Grèce et en Italie, qui séparent ceux qui peuvent prétendre à l’asile des migrants économiques qui sont les plus nombreux. Ceux là, ils n’auront pas plus de droits d’entrer en Europe dans les hot spots.

Libye pour éviter que les personnes prennent des risques fous alors qu’ils ne sont pas éligibles à l’asile. Pour y arriver, il faudra que le calme s’installe dans ce pays l’autre voie pour les africains de l’ouest est la route du Maroc avec des centres d’enregistrement délocalisés situés en Grèce et en Italie, qui séparent ceux qui peuvent prétendre à l’asile des migrants économiques qui sont les plus nombreux. Ceux là, ils n’auront pas plus de droits d’entrer en Europe dans les hot spots.