This article is part of the Sustainable Development Impact Summit

If you have too many things you need to do, it’s best to write them down. Saving the world, it seems, follows the same principle.

In 2015, the UN announced a 17-point to-do list to transform the world for the better. Between them, these sustainable development goals (SDGs) aim to end all poverty, fight inequality and tackle climate change within the next 15 years, in order to fulfil the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

The SDGs were agreed upon at a UN summit in September 2015 by a staggering 193 countries. Announcing them to the world, the UN declared: “We resolve, between now and 2030, to end poverty and hunger everywhere; to combat inequalities within and among countries; to build peaceful, just and inclusive societies; to protect human rights and promote gender equality and the empowerment of women.”

The stated goals are pithy and unequivocal, and contain between them 169 targets to be met by 2030. So what are they?

That’s some to-do list. It’s not the first of its kind, however. In 2000, the UN announced a set of eight millennium development goals (MDGs). There is plenty of overlap between the two lists; the MDGs included pledges to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger, to promote gender equality and to ensure environmental sustainability, for example.

But there are also big differences. The MDGs were aimed only at developing countries, while the SDGs are global. And despite their laudable intentions – not to mention some impressive progress – the MDGs came under fire from several quarters.

They were criticised for a lack of focus on social justice and inequality. The UN’s own assessment of progress towards the MDGs found that the needs of the most vulnerable – the poorest members of society, and those disadvantaged by gender, age, disability or ethnicity – were often overlooked. Another critique offered was that the goals had been drawn up without sufficient consultation of the very people they sought to help.

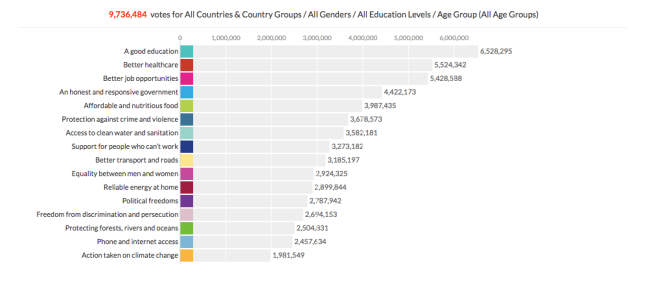

In crafting the SDGs, however, the UN took these criticisms on board. It launched what it called an “unprecedented outreach effort”, in which 5 million people from all over the world were consulted on their visions for the future. Nearly 10 million votes were cast in a survey of people’s priorities – the results are below:

The key to success, according to the UN, will be inclusivity: multi-stakeholder partnerships, as demanded by goal 17, that bring together local and regional governments, the private sector and civil society.

“Collaboration for the SDGs isn’t a nice to have, it’s an imperative. We need everyone: businesses and private investors must join with local stakeholders, governments, philanthropists, and experts,” says Terri Toyota, Head of Sustainable Development at the World Economic Forum. The Forum’s Sustainable Development Impact Summit will take place in September, aiming to make these connections happen.

The SDGs are unquestionably – and necessarily – ambitious, and time is short. With more than 18 months since the goals came into effect, what sort of progress has the world been making? In July this year, the UN published the first annual SDG progress report. The verdict: patchy.

“Implementation has begun, but the clock is ticking,” said UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres in a statement. “This report shows that the rate of progress in many areas is far slower than needed to meet the targets by 2030.”

It’s not all bad news, by any means. Remarkable progress has been achieved in some areas over the past two decades: the report points out that the number of people living in extreme poverty worldwide has fallen sharply from 1.7 billion in 1999 to 767 million in 2913, for example, while the numbers of deaths during pregnancy or childbirth fell by 37% between 2000 and 2015.

But overall, progress has been inconsistent. Goal 4, which calls for quality education for all, has so far enjoyed little success: the proportion of primary school age children out of education globally has remained around 9% since 2008. As for goal 17 – the call for partnerships to meet these targets – the report is blunt: “A stronger commitment to partnership and cooperation is needed to achieve the SDGs.”

There is still a long way to go to reach an ambitious destination. But nobody ever said saving the world would be easy.