If moving forward is the goal, it’s a not a good policy to stand still. Yet we hear little from the government about solutions to Britain’s poor record on social mobility. Earlier this year both the current administration and its predecessors were roundly condemned for their failure to make any headway.

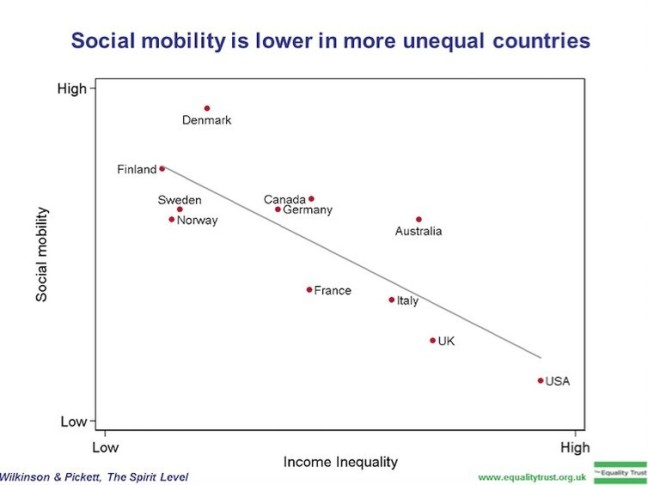

Research has repeatedly shown the clear link between high levels of income inequality and low levels of social mobility. This graph, from our book The Spirit Level shows that far from being the land of opportunity, the US has very low social mobility. You’re much more likely to achieve the “American dream” if you live in Denmark.

British social mobility is damaged by the UK’s high income inequality. Economists have argued that young people from low income families are less likely to invest in their own human capital development (their education) in more unequal societies. Young people are more likely to drop out of high school in more unequal US states or to be NEET (Not in Education, Employment or Training) in more unequal rich countries. Average educational performance on maths and literacy tests is lower in more unequal countries.

It isn’t that young people in unequal societies lack aspirations. In fact, they are more likely to aspire to success. The sad thing is they are less likely to achieve it.

But the ways in which inequality hampers social mobility go far beyond educational involvement and attainment. In unequal societies, more parents will have mental illness or problems with drugs and alcohol. They will be more likely to be burdened by debt and long working hours, adding stress to family life. More young women will have babies as teenagers, more young men will be involved in violence.

Yet if we really tackle inequality, we can expect not only improvements in social mobility but in many other problems at the same time. It’s not enough to focus on educational fixes for social immobility, nor even on poverty reduction and raising the minimum wage. We need to tackle inequality itself, and that includes changing the culture of runaway salaries and bonuses at the top of the income distribution.

For a long time this has felt like an insurmountable challenge, but reducing inequality within and between all countries is now one of the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), to which the UK is a signatory.

There are targets and indicators to monitor progress on reducing inequality and the should be held government accountable for this. Unicef recently reported that the UK ranks 13th among rich countries in meeting the SDGs for children. But it ranked 34th on the hunger goal, and 31st on decent work and economic growth.

As the fifth biggest economy in the world (based on GDP per capita), Britain should be doing better for all its children and young people.

The June report by the Social Mobility Commission concluded that most public policy to improve social mobility under prime ministers Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, David Cameron and Theresa May either failed to improve the situation – or demonstrably made things worse.

Suggested improvements included cross departmental government strategy, ten-year targets for long term change, and a social mobility “test” for all new relevant public policy. It also recommended that public spending be redistributed to address geographical, wealth and generational inequalities. And it advised government coalitions with local councils, communities and employers to create a national effort to improve social mobility.

So far as they go, applying these “lessons” could indeed be helpful. But specific policy recommendations to address social mobility will not reduce the income and wealth inequalities which are at its root.

Appetite for change

So, is there a mandate for change? On the same day as the depressing news about a lack of progress on social mobility, the British Social Attitudes Surveyreleased its annual findings. The results suggested that the public are in favour of progressive change. As many as 48% of people surveyed support higher tax and more public spending, up from 32% at the start of austerity in 2010.

Support for spending on benefits for disabled people is up to 67%, compared with 53% in 2010. And the proportion of people believing benefits claimants were “fiddling” the system dropped to 22% – the lowest level in 30 years. The proportion of the population who thought that government should redistribute income rich to poor was up to 42%, compared to 28% who disagreed. This is a strong mandate for reducing income inequality and ending austerity.

The evidence which shows the damage caused by socioeconomic inequality is mounting. The UK government risks being on the wrong side of history if it continues to fail to address the divide – and condemn us all to its devastating impact.

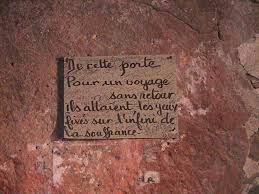

et à lutter contre le racisme et les préjugés d’aujourd’hui. Les visiteurs peuvent évoluer à pied dans le Mémorial pour découvrir trois éléments primaires.

et à lutter contre le racisme et les préjugés d’aujourd’hui. Les visiteurs peuvent évoluer à pied dans le Mémorial pour découvrir trois éléments primaires. l’UNESCO. Il se veut un rappel constant du courage dont ont fait preuve les esclaves, les abolitionnistes et les héros méconnus qui ont contribué à mettre fin à l’oppression de l’esclavage. Il entend aussi faire prendre conscience de tout ce que les esclaves et leurs descendants ont apporté à leurs sociétés.

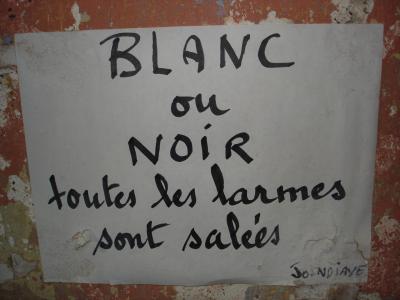

l’UNESCO. Il se veut un rappel constant du courage dont ont fait preuve les esclaves, les abolitionnistes et les héros méconnus qui ont contribué à mettre fin à l’oppression de l’esclavage. Il entend aussi faire prendre conscience de tout ce que les esclaves et leurs descendants ont apporté à leurs sociétés. d’Africains qui ont été emmenés sur des navires négriers dans différentes régions du monde. La couleur blanche évoque la spiritualité africaine. En période de deuil, de chagrin ou de réflexion, les vêtements blancs sont considérés comme les plus appropriés.

d’Africains qui ont été emmenés sur des navires négriers dans différentes régions du monde. La couleur blanche évoque la spiritualité africaine. En période de deuil, de chagrin ou de réflexion, les vêtements blancs sont considérés comme les plus appropriés. de la réconciliation. Les formes triangulaires rappellent le parcours de la traite des esclaves entre les continents. La forme extérieure renvoie l’image d’un bateau, en souvenir des millions d’Africains qui ont été emmenés sur des navires négriers dans différentes régions du monde. La couleur blanche évoque la spiritualité africaine. En période de deuil, de chagrin ou de réflexion, les vêtements blancs sont considérés comme les plus appropriés.

de la réconciliation. Les formes triangulaires rappellent le parcours de la traite des esclaves entre les continents. La forme extérieure renvoie l’image d’un bateau, en souvenir des millions d’Africains qui ont été emmenés sur des navires négriers dans différentes régions du monde. La couleur blanche évoque la spiritualité africaine. En période de deuil, de chagrin ou de réflexion, les vêtements blancs sont considérés comme les plus appropriés.