Expectations are everything, especially in economics.

That’s why a distinct lack of progress in a few basic measures of economic progress, particularly relative to pre-crisis expectations, has left many Americans questioning how much they have personally benefitted from the economic recovery.

A new report from the Roosevelt Institute, a liberal think tank in Washington, highlights a number of ways in which « the recovery since 2009 is, in a sense, a statistical illusion. »

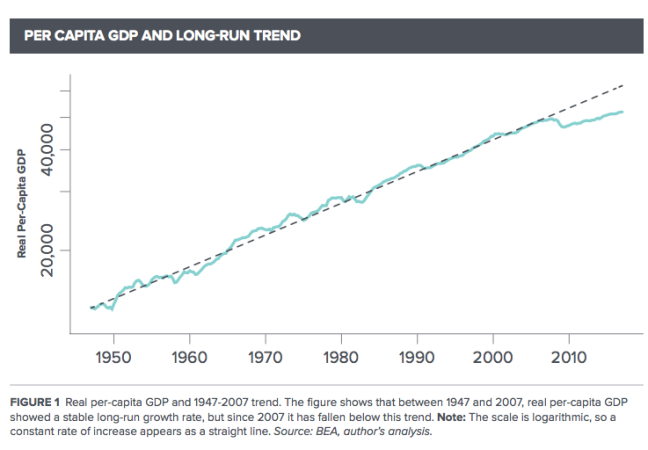

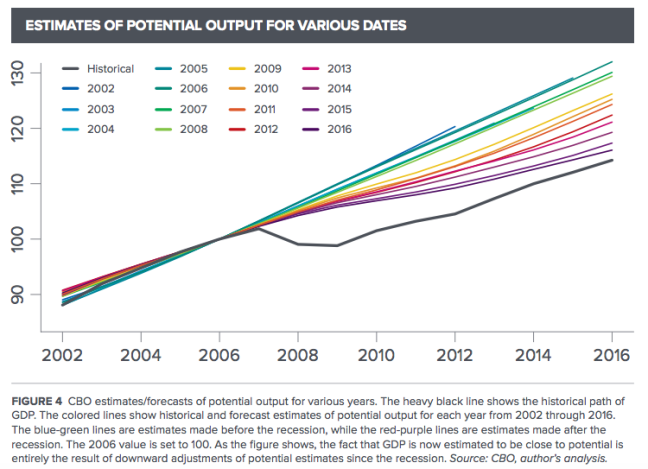

The study finds the nation’s total economic output, its gross domestic product, « remains about 15% below the pre-recession trend, a larger gap than at the bottom of the recession. » The first chart below shows that lag, while the second offers insights into just how badly the crisis dented expectations about the future.

Strong employment gains in recent months have brought the jobless rate down to a historically-low 4.3%. However, this decline has not been accompanied by rising incomes or consumer prices, generally associated with a sustainable economic boom. Some Federal Reserve policymakers have found this trend puzzling, while many labor economists point to underlying weaknesses in the job market, including high levels of underemployment and long-term joblessness, as drags on income.

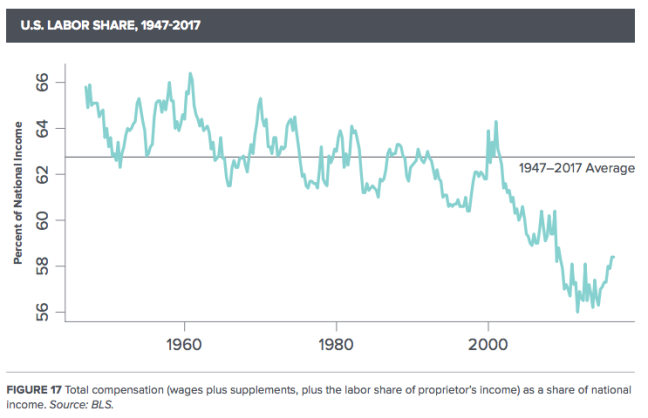

Stagnant wages amid rising profits have meant that the wage share in US national income has fallen from 63% to 57% in the last 15 years, according to the report.

« It is impossible for the wage share to ever rise if the central bank will not allow a period of ‘excessive’ wage growth, » writes J.W. Mason, who authored the report. « A rise in the wage share necessarily requires a period in which wages rise faster than would be consistent with longterm macroeconomic stability. »

In other words, if Fed officials tighten monetary policy at the first sign of wage increases, they will never allow the imbalances that have built up, including deep income disparities, to be torn down. Average hourly earnings rose just 2.5% on a yearly basis in July, nothing to write home about and certainly not enough to begin the ground lost over the last decade and more.

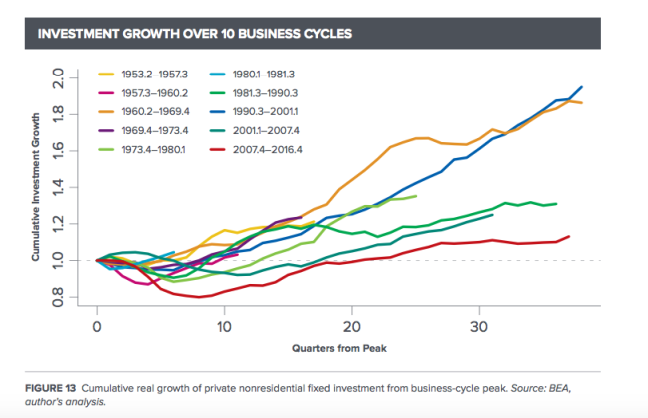

Business investment, which is key to long-run economic growth, has also been dismal during the now eight-year expansion.

« There is no precedent for the weakness of investment in the current cycle. Nearly ten years later, real investment spending remains less than 10% above its 2007 peak, » Mason writes.

« This is slow even relative to the anemic pace of GDP growth, and extremely low by historical standards. In the three previous [economic] cycles lasting that long, real investment spending had increased anywhere from 30% to 80%. Even shorter cycles saw substantially greater investment growth. »

Finally, Mason looks at whether the economy is at risk of running hot, generating inflation, which central bank officials cite to justify interest rate increases. The Fed has raised interest rates three times since December 2015 to a range of 1% to 1.25%.

« On the contrary, we argue, while a myopic focus on one or another data series might support a story of binding supply constraints, the behavior of the economy as a whole is much more consistent with a situation of depressed demand—an extended recession, » the report concludes.

« The overall picture also makes it unclear what actual danger is posed by overheating in the conventional sense. Most of the obvious costs of overheating — higher inflation, higher interest rates, a rising wage share — would be desirable under current circumstances. »