Studies have shown that the quality of our relationships may determine how healthy we are, how well we recover from illness and even how long we live.

However, little is known about how relationships affect sleep. This is especially true for young, unmarried individuals. Teens and emerging adults, in particular, generally do not get the recommended amount of sleep and report a number of sleep problems, such as difficulty falling asleep and daytime fatigue.

Researchers have now started to investigate how relationships with friends and family affect nighttime sleep – particularly among teens and emerging adults.

Results from our recent study with high school students suggest that, even when we go to bed alone, the company we keep by day may determine how well we sleep at night.

Romantic relationships and sleep

Most previous studies have focused on married couples and adults.

In one study of 78 married couples, being worried about a spouse’s availability was linked to more trouble sleeping.

In another study, researchers asked 29 couples to keep diaries on their daily relationship experiences and sleep habits. On days when women reported more positive interactions with their partner, they had more efficient sleep. In other words, they had a higher percentage of actual sleep time compared to the amount of time spent lying in bed.

Interestingly, men also had more efficient sleep when their female partners reported more positive relationship experiences.

Among U.S. college students, a general sense of security in relationships with others was linked to less disturbed sleep – regardless of whether or not students were currently in a committed relationship.

Social ties at college

In our research, we focused on how platonic relationships at college affect how well students slept.

In one study, we asked more than 900 Canadian students about their social life during their first year of college.

One year later, the students who had reported being more engaged in social activities had fewer sleep problems. They had less difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep throughout the night.

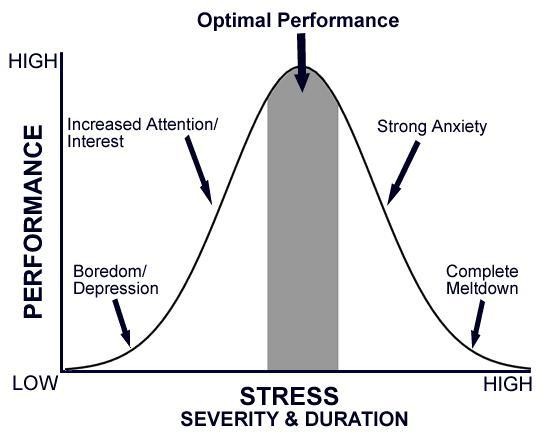

Having a more active and positive social life during the first year of college led to better stress management. That subsequently made it easier for students to fall asleep and stay asleep throughout the night. This pattern was still present in their third year of college.

The reverse was also true: Students with fewer sleep problems during their first year of college reported making more friends and participating in more social activities a year later.

It turns out that having optimal sleep promotes our ability to effectively deal with stress. That, in turn, allows us to be more socially engaged with others.

Friends, family and sleep among children and teens

Many studies ask participants to report on their own sleep. But does this information hold up when we objectively measure the quality of sleep?

In one recent study, we tracked the daily habits of 71 American youth for three days. Students wore a watch-like sleep monitoring device on their non-dominant wrist. This device uses a technique called actigraphy to track activity throughout the night. This eliminated the bias involved in having individuals personally tell us about their sleep.

We measured the total number of hours asleep, how long it took to fall asleep after going to bed and the actual percentage of time spent sleeping relative to how long they lay in bed. We also asked participants to report how much time they spent interacting face to face with friends and family.

Youth fell asleep more easily on days when they spent more time than usual interacting with friends. But they took longer to fall asleep on days when they spent more time than usual with family.

Time spent with family, specifically at night, may include highly emotional events, such as parent-child conflicts, chores or discussions about the day’s events. These family activities may subsequently delay the start of sleep.

We were particularly intrigued by age differences in these associations. Younger participants did not have the same experiences as older participants with respect to sleep efficiency.

Older teens – those over 16.3 years old – who spent several hours face to face with their family had 4 percent more efficient sleep than those who spent less time with their family. However, for children under 12.7 years old, family time did not affect sleep.

Perhaps older teens benefit more from longer family time because of increased academic and social problems, which may require extra family support.

Meanwhile, younger children who spent more time with friends slept 6 percent more efficiently than those who spent less. It may be because this age is a crucial transitioning period, when friends can provide emotional support and facilitate identity development.

Improving our sleep

Teens should heed the importance of their friendships as a vehicle for well-being. For pre-teen children, teens, and emerging adults, friends help regulate negative emotions in a way that consequently improves how well we sleep.

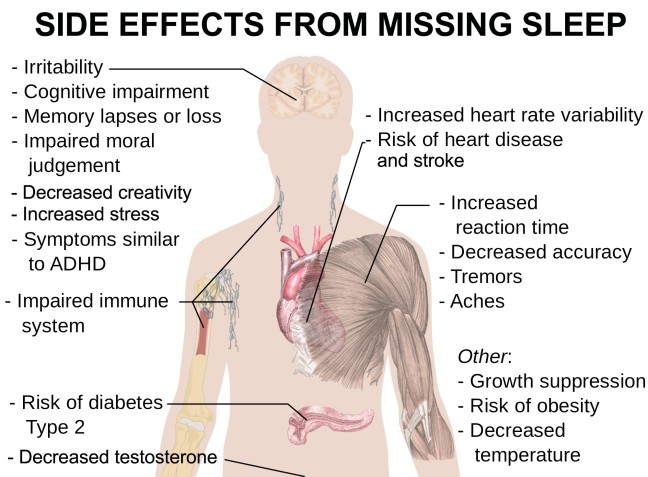

Poor sleep has been linked to a number of mental and physical health issues, including depression and cardiovascular disease.

Parents and teachers should be encouraged to facilitate environments that promote budding friendships among youth. Medical practitioners may also gain additional insight into adolescents’ health by assessing problems with friend and family relationships.