We are starting to witness the penalty for unsustainable lifestyles and patterns of production and consumption. As the human population is exploding, resources are shrinking.

Concerns loom everywhere, from declining pollinators affecting food security, to air and water pollution affecting the quality of life, and land shortage and degradation affecting both agriculture and biodiversity.

These are just some examples of the results of unsustainability. This is an important moment to find solutions for sustainable living, in harmony with Mother Earth.

India is home to one-sixth of the world’s people and it has the densest population. It also has the second-largest population after China, which it will surpass in less than a decade if current trends continue.

India is a country full of diversity and contradictions.

While per-capita emissions are amongst the lowest in the world, it is also the third biggest generator of emissions. Despite being the third largest economy in the world, India also has the largest number of people living below the international poverty line. Because of this sheer size and rapid growth, sustainability is a challenge.

In spite of these challenges, India is a conscious aspirant. It has shown leadership in combating climate change and meeting the Sustainable Developmental Goals (SDGs), as is reflected in many of its developmental schemes.

This commitment was acknowledged by the world in July this year at the UN’s High Level Political Forum, as it presented the Voluntary National Review Report on Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals.

India is one of the least wasteful economies. It has frequently been acknowledged by stakeholders for its cooperation and efforts to promote climate change mitigation, and environmental sustainability; this has been through policy measures, dialogue facilitation between nations, and taking decisive steps, especially after India emerged as a key player in shaping the Paris Agreement, along with adopting energy-efficiency measures.

Sustainability has always been a core component of Indian culture. Its philosophy and values have underscored a sustainable way of life.

For example, the yogic principle of aparigraha, which is a virtue of being non-attached to materialistic possessions, keeping only what is necessary at a certain stage of life. Humans and nature share a harmonious relationship, which goes as far as a reverence for various flora and fauna. This has aided biodiversity conservation efforts.

A great example is of the Bishnoi community in the Jodhpur region, Rajasthan, for whom the protection of wildlife is part of their faith. Yoga and Ayurveda are perhaps among the most well-known ways of holistic Indian living.

Sustainable and environmentally friendly practices and psyches still continue to be part of the lifestyle and culture. India has both a culture of hoarding (in case something might come in useful), and thriftiness (re-use and hand-me-downs). It is not an uncommon sight in an Indian household to witness an old cloth being used as a duster.

Things which have absolutely no value, such as old newspapers and books, or utensils, can be easily sold off to a scrap dealers to be re-used or re-cycled. Bucket baths, sun- drying clothes, and hand-washing dishes are other widespread, sustainable practices. Culturally, there is also an aversion to wasting food.

Rural communities, which constituted about 70% of the Indian population as of 2011, live close to nature and continue to live a simple and frugal lifestyle .

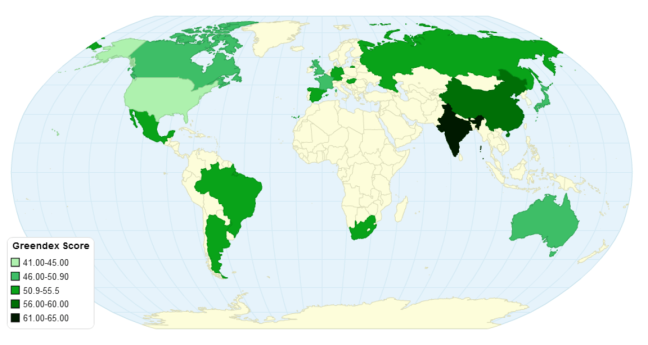

Greendex is an international report on sustainable living. The study compiled by National Geographic and Globescan measures the way consumers are responding to environmental concerns. The scores measure housing, transport, food and goods. India occupies a top spot on this index among 18 contenders, which also include China and the US. In particular, India received high scores in housing, transportation and food choices.

These results show that Indian consumers are most conscious about their environmental footprint and are making the most sustainable choices.

However, as the economy develops and grows further, socio-economic trends are shifting. The country’s achievements so far in no way negate the environmental concerns it still faces.

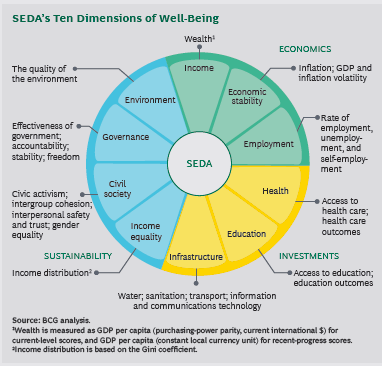

India and the world have a long and challenging way to go in dealing with environmental problems, and learning to live together in sustainable communities. We need to realize that development is more than economic, and sustainable development is a collective responsibility.

India does seem to have taken a lead. As a global family and village, we should come together to learn from each other, and good lessons can be drawn and implemented from both ancient wisdom, and scientific fact.