Ce musée appelé encore couramment musée Guimet, est un musée d’arts asiatiques situé à Paris, 6 Place d’Iéna, dans le 16ᵉ arrondissement. Ce musée a été fondé avec les collections asiatiques d’Émile Guimet qui était un passionné de civilisations qu’il a étudiées et rassemblées au cours de nombreux voyages. Constituant une importante collection dans le but de créer un musée des religions de l’Égypte, de l’Antiquité classique et des pays d’Asie. D’abord présenté à Lyon à partir de 1879, sa collection fut transférée dans un musée inauguré en 1889 qu’il fit construire à Paris. L’institution se consacra de plus en plus à l’Asie tout en conservant une section sur l’Égypte ancienne. Le Musée Guimet s’attache ainsi, depuis plus d’un siècle, à illustrer toutes les civilisations du continent asiatique, de l’Inde au Japon. Il couvre cinq millénaires de son histoire. De la porcelaine chinoise à la statuaire khmère ou afghane en passant par les tissus de l’Inde, la peinture japonaise et coréenne, ou encore les objets rituels tibétains : les témoignages artistiques de chaque culture trouvent leur place dans un parcours riche en chefs-d’œuvre, propice aux mises en perspective et au plaisir de la contemplation esthétique.

Les pays d’Asie représentés par ces collections sont :

Afghanistan Pakistan C’est à l’issue d’une mission sur la frontière indo-afghane, dans la  région de Peshâwar, qu’Alfred Foucher a rapporté quelque cent pièces exposées dès 1900 au Louvre. Elles forment le fonds du Gandhâra au musée Guimet. Cet art du schiste au nord-ouest de l’Inde est un art essentiellement bouddhique. Il raconte pour la

région de Peshâwar, qu’Alfred Foucher a rapporté quelque cent pièces exposées dès 1900 au Louvre. Elles forment le fonds du Gandhâra au musée Guimet. Cet art du schiste au nord-ouest de l’Inde est un art essentiellement bouddhique. Il raconte pour la première fois la légende du Buddha représenté sous une forme humaine et fixe l’iconographie désormais canonique. Il s’épanouit aux environs de l’ère sous des dynasties étrangères, indo-grecques indo-scythe et Kouchane.

première fois la légende du Buddha représenté sous une forme humaine et fixe l’iconographie désormais canonique. Il s’épanouit aux environs de l’ère sous des dynasties étrangères, indo-grecques indo-scythe et Kouchane.

Himalaya est présente dès la fondation du musée Guimet en 1879 à Lyon, avec un petit ensemble d’objets lamaïques, la section himâlayenne se compose aujourd’hui d’un  ensemble d’environ 1600 pièces. Le début de ce siècle est marqué par l’arrivée en 1912 d’une importante collection de bronzes et de peintures, illustrant l’art sino-tibétain du XVIIIe-XIXe siècle, rapportés par Jacques

ensemble d’environ 1600 pièces. Le début de ce siècle est marqué par l’arrivée en 1912 d’une importante collection de bronzes et de peintures, illustrant l’art sino-tibétain du XVIIIe-XIXe siècle, rapportés par Jacques Bacot (1877-1965) de ses missions du Tibet oriental. Cette vision relativement récente et sinisée de l’art du Tibet dominera pendant la majeure partie du siècle. Ce n’est que récemment que les collections du musée permettent d’aborder un panorama plus complet des arts himalayens, notamment dans le domaine népalais.

Bacot (1877-1965) de ses missions du Tibet oriental. Cette vision relativement récente et sinisée de l’art du Tibet dominera pendant la majeure partie du siècle. Ce n’est que récemment que les collections du musée permettent d’aborder un panorama plus complet des arts himalayens, notamment dans le domaine népalais.

Asie Centrale L’importance de l’Asie centrale appelée aussi Sérinde, a été révélée au  début du XXe siècle, par les trouvailles archéologiques qui, sur le tracé de la Route de la Soie, ont mis en valeur un patrimoine bouddhique exceptionnel. Le climat désertique, favorable à la préservation des matières végétales et organiques a permis la conservation de documents uniques, comprenant des manuscrits et des cycles importants d’images cultuelles bouddhiques.

début du XXe siècle, par les trouvailles archéologiques qui, sur le tracé de la Route de la Soie, ont mis en valeur un patrimoine bouddhique exceptionnel. Le climat désertique, favorable à la préservation des matières végétales et organiques a permis la conservation de documents uniques, comprenant des manuscrits et des cycles importants d’images cultuelles bouddhiques.

Asie du Sud-Est La création du département d’art de l’Asie du Sud-est résulte de la réunion de deux grandes collections d’art khmer, entre 1927 et 1931: celle du fonds ancien du musée d’Emile Guimet -avec l’ensemble d’art du Cambodge réuni par Etienne  Aymonier (1844-1929) – et celle de l’ancien Musée Indochinois du Trocadéro dont Louis Delaporte (1842-1925) avait été l’initiateur et le conservateur. Ces collections furent complétées jusqu’en 1936 par les envois de l’Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient dont fit partie le fronton de Banteay Srei MG 18913. L’ensemble de sculptures khmères permet d’illustrer les grandes périodes de l’art du Cambodge, des origines à nos

Aymonier (1844-1929) – et celle de l’ancien Musée Indochinois du Trocadéro dont Louis Delaporte (1842-1925) avait été l’initiateur et le conservateur. Ces collections furent complétées jusqu’en 1936 par les envois de l’Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient dont fit partie le fronton de Banteay Srei MG 18913. L’ensemble de sculptures khmères permet d’illustrer les grandes périodes de l’art du Cambodge, des origines à nos jours et n’a pas son équivalent en Occident. Il est le reflet de la contribution française à la connaissance de cette prestigieuse civilisation. Le Harihara de l’Asram Maha Rosei (MG 14910, VIIe siècle), le fronton de Banteay Srei ( MG 18913, vers 967), ou la tête de Jayavarman VII (P 430, fin du XIIe-début XIIIe siècle) font partie des chefs-d’oeuvre de la sculpture mondiale.

jours et n’a pas son équivalent en Occident. Il est le reflet de la contribution française à la connaissance de cette prestigieuse civilisation. Le Harihara de l’Asram Maha Rosei (MG 14910, VIIe siècle), le fronton de Banteay Srei ( MG 18913, vers 967), ou la tête de Jayavarman VII (P 430, fin du XIIe-début XIIIe siècle) font partie des chefs-d’oeuvre de la sculpture mondiale.

Chine La section chinoise du musée Guimet compte environ 20 000 objets couvrant sept  millénaires d’art chinois, depuis ses origines jusqu’au XVIIIe siècle. Le

millénaires d’art chinois, depuis ses origines jusqu’au XVIIIe siècle. Le domaine archéologique s’ouvre sur la période néolithique avec des jades et des céramiques, se poursuit avec des bronzes des dynasties Shang et Zhou, œuvres majeures auxquelles il convient d’ajouter d’importantes collections d’éléments de harnachement et de charrerie, de miroirs et d’agrafes en bronze ainsi que de numismatique et de laques.

domaine archéologique s’ouvre sur la période néolithique avec des jades et des céramiques, se poursuit avec des bronzes des dynasties Shang et Zhou, œuvres majeures auxquelles il convient d’ajouter d’importantes collections d’éléments de harnachement et de charrerie, de miroirs et d’agrafes en bronze ainsi que de numismatique et de laques.

Corée Le fonds coréen au musée Guimet renvoie à la mission qu’effectue Charles Varat en 1888, de Séoul à Pusan, sous couvert du Ministère de l’Instruction Publique et des  Beaux-arts. Réalisée avec l’aide de Victor Collin de Plancy, premier représentant diplomatique français à la cour de Séoul, et celle du gouvernement de la Corée Choson (1392-1910), elle entend faire connaître au public parisien la culture d’un pays encore très mal connu. Dès 1893, est ouverte au musée une galerie coréenne, à laquelle a travaillé Varat, assisté d’Hong Jeong-ou. Présentant les arts de la Corée, sous ses aspects

Beaux-arts. Réalisée avec l’aide de Victor Collin de Plancy, premier représentant diplomatique français à la cour de Séoul, et celle du gouvernement de la Corée Choson (1392-1910), elle entend faire connaître au public parisien la culture d’un pays encore très mal connu. Dès 1893, est ouverte au musée une galerie coréenne, à laquelle a travaillé Varat, assisté d’Hong Jeong-ou. Présentant les arts de la Corée, sous ses aspects  les plus variés (peinture et mobilier, costume et céramique), elle subsistera jusqu’en 1918, date de la première rénovation générale du musée. En revanche, les collections qui arrivent par le Louvre proviennent le plus souvent d’anciennes collections japonaises (bannière d’époque Koryo, 13ème – 14ème s., ou bronze doré sur le thème du bodhisattva méditant, 6ème s.).

les plus variés (peinture et mobilier, costume et céramique), elle subsistera jusqu’en 1918, date de la première rénovation générale du musée. En revanche, les collections qui arrivent par le Louvre proviennent le plus souvent d’anciennes collections japonaises (bannière d’époque Koryo, 13ème – 14ème s., ou bronze doré sur le thème du bodhisattva méditant, 6ème s.).

Inde La section indienne du musée Guimet est constituée d’une part, ![IMG_0314[1]](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_03141.jpg?w=88&h=88) de sculptures (terre cuite, pierre, bronze et bois) s’échelonnant du

de sculptures (terre cuite, pierre, bronze et bois) s’échelonnant du![IMG_0310[1]](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_03101.jpg?w=73&h=73) IIIe millénaire avant notre ère jusqu’aux XVIII-XIXes siècles de notre ère, et d’autre part, de peintures mobiles ou miniatures, du XVe au XIXe siècle.

IIIe millénaire avant notre ère jusqu’aux XVIII-XIXes siècles de notre ère, et d’autre part, de peintures mobiles ou miniatures, du XVe au XIXe siècle.

Japon Les collections de la section japonaise, comptant environ 11000 oeuvres, offrent ![IMG_0451[1]](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_04511.jpg?w=648) un panorama extrêmement riche et diversifié de l’art japonais depuis sa naissance, au cours des IIIe-IIe millénaires av. notre ère, jusqu’à l’avènement de l’ère Meiji (1868).

un panorama extrêmement riche et diversifié de l’art japonais depuis sa naissance, au cours des IIIe-IIe millénaires av. notre ère, jusqu’à l’avènement de l’ère Meiji (1868).

![IMG_0461[1].JPG](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_04611.jpg?w=4032)

Textiles La collection de textiles du musée Guimet provenant essentiellement du fonds  de l’Association pour l’Etude et la Documentation des Textiles d’Asie (AEDTA) fondée en 1979 par Krishnâ Riboud à partir de sa

de l’Association pour l’Etude et la Documentation des Textiles d’Asie (AEDTA) fondée en 1979 par Krishnâ Riboud à partir de sa collection personnelle, complète les collections des pays concernés. Il s’agissait à l’époque de la plus importante collection privée consacrée aux textiles d’Asie. En 1990, Krishnâ Riboud a souhaité effectuer une première donation de 150 pièces. Conformément à son souhait, en 2003, le reste de la collection – soit près de 3 800 pièces auxquelles s’ajoutent 150 objets (aquarelles, objets témoignant des techniques de tissage) – a été légué au musée

collection personnelle, complète les collections des pays concernés. Il s’agissait à l’époque de la plus importante collection privée consacrée aux textiles d’Asie. En 1990, Krishnâ Riboud a souhaité effectuer une première donation de 150 pièces. Conformément à son souhait, en 2003, le reste de la collection – soit près de 3 800 pièces auxquelles s’ajoutent 150 objets (aquarelles, objets témoignant des techniques de tissage) – a été légué au musée qui se trouve dorénavant parmi les mieux dotés au monde dans ce domaine. Outre son importance scientifique et numérique, le legs de 2003 permet de conserver à la collection toute sa cohérence et son histoire.

qui se trouve dorénavant parmi les mieux dotés au monde dans ce domaine. Outre son importance scientifique et numérique, le legs de 2003 permet de conserver à la collection toute sa cohérence et son histoire.

Depuis 2008, le musée s’est ouvert à l’art contemporain afin d’instaurer un dialogue entre ses œuvres millénaires et la production artistique contemporaine asiatique. Pour cette année, carte blanche a été donnée à l’une des plus jeunes (et talentueuses) artistes  françaises. Prune Nourry c’est d’ailleurs la plus jeune artiste qui ait jamais exposé dans l’illustre musée Guimet. Du haut de ses 32 ans, l’artiste nous livre une réflexion des plus touchantes et pertinentes sur l’avenir de l’humanité. Pour ceux qui connaissent déjà l’artiste, rassurez-vous, vous pourrez admirer l’une de ses œuvres phares, à savoir ses Terracotta Daughters. Si l’œuvre intégrale, composée de 108 sculptures en terre cuite, a

françaises. Prune Nourry c’est d’ailleurs la plus jeune artiste qui ait jamais exposé dans l’illustre musée Guimet. Du haut de ses 32 ans, l’artiste nous livre une réflexion des plus touchantes et pertinentes sur l’avenir de l’humanité. Pour ceux qui connaissent déjà l’artiste, rassurez-vous, vous pourrez admirer l’une de ses œuvres phares, à savoir ses Terracotta Daughters. Si l’œuvre intégrale, composée de 108 sculptures en terre cuite, a été ensevelie dans un lieu secret en Chine. Ici, on pourra admirer leurs huit originaux, et autant vous dire que l’émotion est ici à son comble face à ses collégiennes grandeur nature, une référence aux soldats du premier empereur, dans une version féminine qui nous rappelle les drames de la politique chinoise de l’enfant unique, et les fantômes des centaines de millions de filles qui ne verront jamais le jour.

été ensevelie dans un lieu secret en Chine. Ici, on pourra admirer leurs huit originaux, et autant vous dire que l’émotion est ici à son comble face à ses collégiennes grandeur nature, une référence aux soldats du premier empereur, dans une version féminine qui nous rappelle les drames de la politique chinoise de l’enfant unique, et les fantômes des centaines de millions de filles qui ne verront jamais le jour.

On a admiré aussi ses Holy Daughters, ce sont ces sculptures hybrides, une forme de synthèse troublante entre une jeune fille et une vache. Dit comme ça, ça peut choquer, ![IMG_0297[1].JPG](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_02971.jpg?w=648) mais l’artiste nous chahute volontairement, pour souligner le paradoxe qui existe en Inde, entre la femme, source de fécondité peu considérée, et l’animal sacré, symbole de fertilité, vénéré. Une manière de dénoncer le paradoxe qu’il y a à sacraliser la vache au détriment d’une petite fille, appelée à devenir mère un jour.

mais l’artiste nous chahute volontairement, pour souligner le paradoxe qui existe en Inde, entre la femme, source de fécondité peu considérée, et l’animal sacré, symbole de fertilité, vénéré. Une manière de dénoncer le paradoxe qu’il y a à sacraliser la vache au détriment d’une petite fille, appelée à devenir mère un jour.

Alors d’habitude ici, les cartes blanches à l’art contemporain sont cantonnées à la coupole, au 4ème et dernier étage du musée. L’artiste ne déroge pas à la règle en  installant une tête de bouddha colossale, de plus de 3 mètres de haut, plantée de milliers de bâtons d’encens, comme autant d’aiguilles réparatrices. Un Bouddha monumental qui fait office de fil rouge tout au long de l’exposition pour aider le visiteur à comprendre l’histoire des civilisations asiatiques. Et ce Bouddha déborde de toutes parts et s’installe à chaque étage du musée, en référence à celui détruit en 2001 par les Talibans, un colosse de près de 40 mètres. On découvrira ainsi au 1erétage sa main monumentale, de près de 5 mètres de haut, on ses pieds au rez-de-chaussée, dans des dimensions absolument vertigineuses.

installant une tête de bouddha colossale, de plus de 3 mètres de haut, plantée de milliers de bâtons d’encens, comme autant d’aiguilles réparatrices. Un Bouddha monumental qui fait office de fil rouge tout au long de l’exposition pour aider le visiteur à comprendre l’histoire des civilisations asiatiques. Et ce Bouddha déborde de toutes parts et s’installe à chaque étage du musée, en référence à celui détruit en 2001 par les Talibans, un colosse de près de 40 mètres. On découvrira ainsi au 1erétage sa main monumentale, de près de 5 mètres de haut, on ses pieds au rez-de-chaussée, dans des dimensions absolument vertigineuses.

Avec ses œuvres, l’artiste réveille les silences millénaires et enchante notre visite dans un dialogue des plus poétiques avec les collections historiques du musée, auxquelles elle apporte une lumière nouvelle.

L’ORS D’ASIE qui dure jusqu’au 18 septembre 2017, est une exposition d’envergure. Sur ce continent asiatique où l’or tient une place centrale. Présent dans la symbolique ![IMG_0502[1]](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_05021.jpg?w=225&h=300) bouddhique, le bouddhisme tantrique et, pour une moindre part, l’hindouisme et le jainisme. Pour cette occasion le musée Guimet a choisi d’interroger ses propres

bouddhique, le bouddhisme tantrique et, pour une moindre part, l’hindouisme et le jainisme. Pour cette occasion le musée Guimet a choisi d’interroger ses propres ![IMG_0531[1]](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_05311.jpg?w=168&h=224) collections, dont certaines, ressorties des réserves, restaurées ou nouvellement acquises forment un ensemble de 113 chefs-d’œuvre. C’est avec un regard d’orfèvre que le musée explore et pose ainsi le cadre des échanges du métal inaltérable et des raisons de sa rareté, qu’il soit poudre d’or au Japon, en Chine ou en Corée, émissions monétaires dans l’Afghanistan kouchane ou parure de maharajahs indiens. Les techniques d’extraction et du travail de l’or sont abordées en préambule, avant qu’un florilège de splendeurs ne raconte sa fabuleuse épopée, les raisons de l’attrait et du pouvoir de séduction qu’il suscita en Asie, mille et une histoires en or.

collections, dont certaines, ressorties des réserves, restaurées ou nouvellement acquises forment un ensemble de 113 chefs-d’œuvre. C’est avec un regard d’orfèvre que le musée explore et pose ainsi le cadre des échanges du métal inaltérable et des raisons de sa rareté, qu’il soit poudre d’or au Japon, en Chine ou en Corée, émissions monétaires dans l’Afghanistan kouchane ou parure de maharajahs indiens. Les techniques d’extraction et du travail de l’or sont abordées en préambule, avant qu’un florilège de splendeurs ne raconte sa fabuleuse épopée, les raisons de l’attrait et du pouvoir de séduction qu’il suscita en Asie, mille et une histoires en or.

C’est le bouddhisme qui ouvre à l’or de vastes horizons aux résonances toutes ![IMG_0552[1].JPG](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_05521.jpg?w=4032) symboliques : comment la lumineuse carnation du Bouddha ne pourrait être mieux évoquée que par l’or ? Vecteur d’éternité, l’or tient dans la parure funéraire, comme dans la conservation de la mémoire, une fonction de premier ordre, offrant à la statuaire de saisir de façon frappante ces facteurs d’unité à l’échelle du continent asiatique, de telle sorte que lorsque l’or est absent, le bronze ou le bois doré en jouent les substituts.

symboliques : comment la lumineuse carnation du Bouddha ne pourrait être mieux évoquée que par l’or ? Vecteur d’éternité, l’or tient dans la parure funéraire, comme dans la conservation de la mémoire, une fonction de premier ordre, offrant à la statuaire de saisir de façon frappante ces facteurs d’unité à l’échelle du continent asiatique, de telle sorte que lorsque l’or est absent, le bronze ou le bois doré en jouent les substituts.

Quand l’or fréquemment mentionné est stimulé dans les sutras, les vêtements rapiécés des compagnons du bouddha historique deviennent les prétextes à la création de luxueux patchworks à bande d’or, tout comme l’or présent dans le costume de Lucknow, ![IMG_0558[1].JPG](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_05581.jpg?w=4032) dernier bastion de l’Inde moghole. Promesse d’éternité, l’or défie le temps humain et joue la transmission : l’empereur de Chine, Qianlong, avec ses calligraphies à l’encre d’or des plaques de jade, ses propres écrits sur l’éthique et la philosophie en politique, à l’occasion de son quatre-vingtième anniversaire. Investi de la symbolique du pouvoir et de la richesse, l’or et ses fastes sont évoqués à travers le matériel archéologique mais aussi la production d’objets de luxe dans l’Inde moghole. En Afghanistan, durant la dynastie kouchane (1er-3e siècle), le monnayage en or apparaît et la monnaie d’or qui fait référence à l’irruption des nomades dans le monde sédentaire, exprimait aussi l’immense prestige et la puissance du souverain, l’Altaï étant la source de l’or. En écho au monde des steppes, certains objets archéologiques tel que la couronne typique du royaume de Silla (5e-6e siècle) provenant d’une tombe de Kyongung en Corée, attestait de l’importance du faste au temps des Trois Royaumes.

dernier bastion de l’Inde moghole. Promesse d’éternité, l’or défie le temps humain et joue la transmission : l’empereur de Chine, Qianlong, avec ses calligraphies à l’encre d’or des plaques de jade, ses propres écrits sur l’éthique et la philosophie en politique, à l’occasion de son quatre-vingtième anniversaire. Investi de la symbolique du pouvoir et de la richesse, l’or et ses fastes sont évoqués à travers le matériel archéologique mais aussi la production d’objets de luxe dans l’Inde moghole. En Afghanistan, durant la dynastie kouchane (1er-3e siècle), le monnayage en or apparaît et la monnaie d’or qui fait référence à l’irruption des nomades dans le monde sédentaire, exprimait aussi l’immense prestige et la puissance du souverain, l’Altaï étant la source de l’or. En écho au monde des steppes, certains objets archéologiques tel que la couronne typique du royaume de Silla (5e-6e siècle) provenant d’une tombe de Kyongung en Corée, attestait de l’importance du faste au temps des Trois Royaumes. ![IMG_0563[1]](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_05631.jpg?w=648) Au Japon, l’or habille de grâce les éblouissants objets de laque, les paravents et textiles de l’apogée bourgeoise, les plus raffinés comme les plus frivoles du monde flottant, rappelant ici que la fascination pour le métal magique n’empêche pas le vieil adage : « tout ce qui brille n’est pas d’or ».

Au Japon, l’or habille de grâce les éblouissants objets de laque, les paravents et textiles de l’apogée bourgeoise, les plus raffinés comme les plus frivoles du monde flottant, rappelant ici que la fascination pour le métal magique n’empêche pas le vieil adage : « tout ce qui brille n’est pas d’or ».

L’exposition des Paysages japonais, de Hokusai à Hasui qui continue jusqu’au 2 octobre 2017 est constituée d’une centaine d’estampes japonaises issues du fonds de la collection nationale, dont la célèbre Grande vague de Hokusai (Sous la vague au large de Kanagawa, Kanagawa oki namiura), le Musée nous entraîne dans un éblouissant voyage, celui de la contemplation du paysage dans son plein épanouissement. Visions panoramiques et  impressionnistes qui exaltent le passage des saisons et les lieux célèbres du Japon, visions urbaines et descriptions d’itinéraires poétiques au début de l’époque Edo, ou encore scènes de genre et intimistes dans l’art des grands maîtres Hokusai et Hiroshige qui ont su renouveler l’art de l’Ukiyo-e, cette exposition méditation présentera aussi des estampes nouvellement acquises de la période moderne, dont celles très graphiques d’Hasui Kawase. Véritable palette documentaire toute en finesse et aux subtiles couleurs, les estampes présentées couvriront une période de trois siècles et montreront la réalité d’une géographie et de ses territoires. Une ode à la dimension divine du spectacle de la nature dans le respect d’une harmonie fondamentale entre ses éléments et celle de l’être humain, où comment le rêve et le réel appartiennent à une même vision. L’exposition interroge la notion de paysage dans l’estampe et la considère dans un contexte plus général, celui de l’itinérance et de la fascination pour la ville, telle que celle-ci se développera et se perpétuera durant le 19e siècle. Avec l’idée d’une déambulation poétique, d’une gravitation autour d’une cité, qui introduit la notion philosophique du temps qui passe, c’est une présentation autant spatiale que temporaire qui en sera le propos naturaliste.

impressionnistes qui exaltent le passage des saisons et les lieux célèbres du Japon, visions urbaines et descriptions d’itinéraires poétiques au début de l’époque Edo, ou encore scènes de genre et intimistes dans l’art des grands maîtres Hokusai et Hiroshige qui ont su renouveler l’art de l’Ukiyo-e, cette exposition méditation présentera aussi des estampes nouvellement acquises de la période moderne, dont celles très graphiques d’Hasui Kawase. Véritable palette documentaire toute en finesse et aux subtiles couleurs, les estampes présentées couvriront une période de trois siècles et montreront la réalité d’une géographie et de ses territoires. Une ode à la dimension divine du spectacle de la nature dans le respect d’une harmonie fondamentale entre ses éléments et celle de l’être humain, où comment le rêve et le réel appartiennent à une même vision. L’exposition interroge la notion de paysage dans l’estampe et la considère dans un contexte plus général, celui de l’itinérance et de la fascination pour la ville, telle que celle-ci se développera et se perpétuera durant le 19e siècle. Avec l’idée d’une déambulation poétique, d’une gravitation autour d’une cité, qui introduit la notion philosophique du temps qui passe, c’est une présentation autant spatiale que temporaire qui en sera le propos naturaliste.

L’exposition Porcelaine, chefs-d’œuvre de la collection Ise Les chefs-d’œuvre de céramique chinoise de la collection Ise sont exposés pour la première fois en France. Monochromes, céladons, « trois couleurs », porcelaines bleu et blanc, etc., au-delà d’un parcours esthétique et historique. Riche agro-industriel et philanthrope, Hikonobu Ise commence à constituer sa collection de céramiques il y a une trentaine d’années, afin, dit-il, d’éviter la dispersion, d’assurer la pérennité et de présenter au public du monde entier ces chefs-d’œuvre de la haute civilisation chinoise qu’il admire tant.

Cette collection, qui couvre les productions du 5e siècle avant notre ère jusqu’au 19e siècle, des périodes antiques aux Qing (1644-1911), a acquis au fil du temps un grand rayonnement. Si la sélection des pièces maîtresses de la collection Ise, présentée dans les salles rénovées du rez-de-chaussée de l’Hôtel d’Heidelbach, permet de dresser un panorama de l’évolution des techniques et des décors de l’art céramique chinois, elle est aussi l’occasion de saisir ce phénomène remarquable qu’est le goût japonais pour la céramique chinoise. Depuis l’époque de Kamakura (1185-1333), des céramiques chinoises  sont importées par l’Archipel, pour la cérémonie du thé, que les Japonais ont transformée en un art de vivre à forte dimension cultuelle. C’est dans cette filiation que s’inscrit le collectionnisme d’Hikonobu Ise, porté notamment par son admiration pour la culture lettrée chinoise. Il raconte ainsi que chaque semaine, il sort de son étui l’un de ces objets, pour le contempler en dégustant un thé ; le sentiment de joie qu’il en ressent alors est au-delà du simple moment de détente. Ses choix semblent en effet guidés en premier lieu par l’émotion procurée par des objets qui « ont attrapé [son] cœur » et par le dialogue esthétique qui s’instaure avec l’œuvre dès le « premier regard » : face à une céramique Ming, représentant un combat de coqs, il fut ainsi « totalement ébloui et [se sentit] presque en état d’ébriété pendant les six mois qui ont suivi ». Le respect du Beau et la nécessité de réaliser des emballages propres à protéger les objets précieux, notamment des dangers sismiques, ont permis de conserver de manière exceptionnelle ces céramiques, dont les vibrants reflets des glaçures, les couleurs chatoyantes des émaux, les subtilités des décors sont d’une telle qualité que ces œuvres de plusieurs siècles semblent être à peine sorties du four. Présenter cette collection, c’est ainsi convier chacun à un voyage sensoriel et esthétique, dans l’intimité d’un passionné.

sont importées par l’Archipel, pour la cérémonie du thé, que les Japonais ont transformée en un art de vivre à forte dimension cultuelle. C’est dans cette filiation que s’inscrit le collectionnisme d’Hikonobu Ise, porté notamment par son admiration pour la culture lettrée chinoise. Il raconte ainsi que chaque semaine, il sort de son étui l’un de ces objets, pour le contempler en dégustant un thé ; le sentiment de joie qu’il en ressent alors est au-delà du simple moment de détente. Ses choix semblent en effet guidés en premier lieu par l’émotion procurée par des objets qui « ont attrapé [son] cœur » et par le dialogue esthétique qui s’instaure avec l’œuvre dès le « premier regard » : face à une céramique Ming, représentant un combat de coqs, il fut ainsi « totalement ébloui et [se sentit] presque en état d’ébriété pendant les six mois qui ont suivi ». Le respect du Beau et la nécessité de réaliser des emballages propres à protéger les objets précieux, notamment des dangers sismiques, ont permis de conserver de manière exceptionnelle ces céramiques, dont les vibrants reflets des glaçures, les couleurs chatoyantes des émaux, les subtilités des décors sont d’une telle qualité que ces œuvres de plusieurs siècles semblent être à peine sorties du four. Présenter cette collection, c’est ainsi convier chacun à un voyage sensoriel et esthétique, dans l’intimité d’un passionné.

Le musée Guimet est un lieu magique, il nous permet de comprendre au mieux, cette Asie complexe, laborieuse et mystérieuse qui très souvent nous échappe. Sa richesse aussi vieille que son histoire nous émerveille depuis toujours. Mes ami(e)s, si vous passez par Paris, vous qui aimez le monde, allez au musée Guimet vous aimerez encore plus la vie, ceux et celles qui la rendent aussi belle, ce sont nos ami(e)s de cette belle Asie.

région de Peshâwar, qu’Alfred Foucher a rapporté quelque cent pièces exposées dès 1900 au Louvre. Elles forment le fonds du Gandhâra au musée Guimet. Cet art du schiste au nord-ouest de l’Inde est un art essentiellement bouddhique. Il raconte pour la

région de Peshâwar, qu’Alfred Foucher a rapporté quelque cent pièces exposées dès 1900 au Louvre. Elles forment le fonds du Gandhâra au musée Guimet. Cet art du schiste au nord-ouest de l’Inde est un art essentiellement bouddhique. Il raconte pour la première fois la légende du Buddha représenté sous une forme humaine et fixe l’iconographie désormais canonique. Il s’épanouit aux environs de l’ère sous des dynasties étrangères, indo-grecques indo-scythe et Kouchane.

première fois la légende du Buddha représenté sous une forme humaine et fixe l’iconographie désormais canonique. Il s’épanouit aux environs de l’ère sous des dynasties étrangères, indo-grecques indo-scythe et Kouchane. ensemble d’environ 1600 pièces. Le début de ce siècle est marqué par l’arrivée en 1912 d’une importante collection de bronzes et de peintures, illustrant l’art sino-tibétain du XVIIIe-XIXe siècle, rapportés par Jacques

ensemble d’environ 1600 pièces. Le début de ce siècle est marqué par l’arrivée en 1912 d’une importante collection de bronzes et de peintures, illustrant l’art sino-tibétain du XVIIIe-XIXe siècle, rapportés par Jacques Bacot (1877-1965) de ses missions du Tibet oriental. Cette vision relativement récente et sinisée de l’art du Tibet dominera pendant la majeure partie du siècle. Ce n’est que récemment que les collections du musée permettent d’aborder un panorama plus complet des arts himalayens, notamment dans le domaine népalais.

Bacot (1877-1965) de ses missions du Tibet oriental. Cette vision relativement récente et sinisée de l’art du Tibet dominera pendant la majeure partie du siècle. Ce n’est que récemment que les collections du musée permettent d’aborder un panorama plus complet des arts himalayens, notamment dans le domaine népalais. début du XXe siècle, par les trouvailles archéologiques qui, sur le tracé de la Route de la Soie, ont mis en valeur un patrimoine bouddhique exceptionnel. Le climat désertique, favorable à la préservation des matières végétales et organiques a permis la conservation de documents uniques, comprenant des manuscrits et des cycles importants d’images cultuelles bouddhiques.

début du XXe siècle, par les trouvailles archéologiques qui, sur le tracé de la Route de la Soie, ont mis en valeur un patrimoine bouddhique exceptionnel. Le climat désertique, favorable à la préservation des matières végétales et organiques a permis la conservation de documents uniques, comprenant des manuscrits et des cycles importants d’images cultuelles bouddhiques. Aymonier (1844-1929) – et celle de l’ancien Musée Indochinois du Trocadéro dont Louis Delaporte (1842-1925) avait été l’initiateur et le conservateur. Ces collections furent complétées jusqu’en 1936 par les envois de l’Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient dont fit partie le fronton de Banteay Srei MG 18913. L’ensemble de sculptures khmères permet d’illustrer les grandes périodes de l’art du Cambodge, des origines à nos

Aymonier (1844-1929) – et celle de l’ancien Musée Indochinois du Trocadéro dont Louis Delaporte (1842-1925) avait été l’initiateur et le conservateur. Ces collections furent complétées jusqu’en 1936 par les envois de l’Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient dont fit partie le fronton de Banteay Srei MG 18913. L’ensemble de sculptures khmères permet d’illustrer les grandes périodes de l’art du Cambodge, des origines à nos jours et n’a pas son équivalent en Occident. Il est le reflet de la contribution française à la connaissance de cette prestigieuse civilisation. Le Harihara de l’Asram Maha Rosei (MG 14910, VIIe siècle), le fronton de Banteay Srei ( MG 18913, vers 967), ou la tête de Jayavarman VII (P 430, fin du XIIe-début XIIIe siècle) font partie des chefs-d’oeuvre de la sculpture mondiale.

jours et n’a pas son équivalent en Occident. Il est le reflet de la contribution française à la connaissance de cette prestigieuse civilisation. Le Harihara de l’Asram Maha Rosei (MG 14910, VIIe siècle), le fronton de Banteay Srei ( MG 18913, vers 967), ou la tête de Jayavarman VII (P 430, fin du XIIe-début XIIIe siècle) font partie des chefs-d’oeuvre de la sculpture mondiale. millénaires d’art chinois, depuis ses origines jusqu’au XVIIIe siècle. Le

millénaires d’art chinois, depuis ses origines jusqu’au XVIIIe siècle. Le domaine archéologique s’ouvre sur la période néolithique avec des jades et des céramiques, se poursuit avec des bronzes des dynasties Shang et Zhou, œuvres majeures auxquelles il convient d’ajouter d’importantes collections d’éléments de harnachement et de charrerie, de miroirs et d’agrafes en bronze ainsi que de numismatique et de laques.

domaine archéologique s’ouvre sur la période néolithique avec des jades et des céramiques, se poursuit avec des bronzes des dynasties Shang et Zhou, œuvres majeures auxquelles il convient d’ajouter d’importantes collections d’éléments de harnachement et de charrerie, de miroirs et d’agrafes en bronze ainsi que de numismatique et de laques. Beaux-arts. Réalisée avec l’aide de Victor Collin de Plancy, premier représentant diplomatique français à la cour de Séoul, et celle du gouvernement de la Corée Choson (1392-1910), elle entend faire connaître au public parisien la culture d’un pays encore très mal connu. Dès 1893, est ouverte au musée une galerie coréenne, à laquelle a travaillé Varat, assisté d’Hong Jeong-ou. Présentant les arts de la Corée, sous ses aspects

Beaux-arts. Réalisée avec l’aide de Victor Collin de Plancy, premier représentant diplomatique français à la cour de Séoul, et celle du gouvernement de la Corée Choson (1392-1910), elle entend faire connaître au public parisien la culture d’un pays encore très mal connu. Dès 1893, est ouverte au musée une galerie coréenne, à laquelle a travaillé Varat, assisté d’Hong Jeong-ou. Présentant les arts de la Corée, sous ses aspects  les plus variés (peinture et mobilier, costume et céramique), elle subsistera jusqu’en 1918, date de la première rénovation générale du musée. En revanche, les collections qui arrivent par le Louvre proviennent le plus souvent d’anciennes collections japonaises (bannière d’époque Koryo, 13ème – 14ème s., ou bronze doré sur le thème du bodhisattva méditant, 6ème s.).

les plus variés (peinture et mobilier, costume et céramique), elle subsistera jusqu’en 1918, date de la première rénovation générale du musée. En revanche, les collections qui arrivent par le Louvre proviennent le plus souvent d’anciennes collections japonaises (bannière d’époque Koryo, 13ème – 14ème s., ou bronze doré sur le thème du bodhisattva méditant, 6ème s.).![IMG_0314[1]](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_03141.jpg?w=88&h=88) de sculptures (terre cuite, pierre, bronze et bois) s’échelonnant du

de sculptures (terre cuite, pierre, bronze et bois) s’échelonnant du![IMG_0310[1]](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_03101.jpg?w=73&h=73) IIIe millénaire avant notre ère jusqu’aux XVIII-XIXes siècles de notre ère, et d’autre part, de peintures mobiles ou miniatures, du XVe au XIXe siècle.

IIIe millénaire avant notre ère jusqu’aux XVIII-XIXes siècles de notre ère, et d’autre part, de peintures mobiles ou miniatures, du XVe au XIXe siècle.![IMG_0451[1]](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_04511.jpg?w=648) un panorama extrêmement riche et diversifié de l’art japonais depuis sa naissance, au cours des IIIe-IIe millénaires av. notre ère, jusqu’à l’avènement de l’ère Meiji (1868).

un panorama extrêmement riche et diversifié de l’art japonais depuis sa naissance, au cours des IIIe-IIe millénaires av. notre ère, jusqu’à l’avènement de l’ère Meiji (1868).![IMG_0461[1].JPG](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_04611.jpg?w=4032)

de l’Association pour l’Etude et la Documentation des Textiles d’Asie (AEDTA) fondée en 1979 par Krishnâ Riboud à partir de sa

de l’Association pour l’Etude et la Documentation des Textiles d’Asie (AEDTA) fondée en 1979 par Krishnâ Riboud à partir de sa collection personnelle, complète les collections des pays concernés. Il s’agissait à l’époque de la plus importante collection privée consacrée aux textiles d’Asie. En 1990, Krishnâ Riboud a souhaité effectuer une première donation de 150 pièces. Conformément à son souhait, en 2003, le reste de la collection – soit près de 3 800 pièces auxquelles s’ajoutent 150 objets (aquarelles, objets témoignant des techniques de tissage) – a été légué au musée

collection personnelle, complète les collections des pays concernés. Il s’agissait à l’époque de la plus importante collection privée consacrée aux textiles d’Asie. En 1990, Krishnâ Riboud a souhaité effectuer une première donation de 150 pièces. Conformément à son souhait, en 2003, le reste de la collection – soit près de 3 800 pièces auxquelles s’ajoutent 150 objets (aquarelles, objets témoignant des techniques de tissage) – a été légué au musée qui se trouve dorénavant parmi les mieux dotés au monde dans ce domaine. Outre son importance scientifique et numérique, le legs de 2003 permet de conserver à la collection toute sa cohérence et son histoire.

qui se trouve dorénavant parmi les mieux dotés au monde dans ce domaine. Outre son importance scientifique et numérique, le legs de 2003 permet de conserver à la collection toute sa cohérence et son histoire. françaises. Prune Nourry c’est d’ailleurs la plus jeune artiste qui ait jamais exposé dans l’illustre musée Guimet. Du haut de ses 32 ans, l’artiste nous livre une réflexion des plus touchantes et pertinentes sur l’avenir de l’humanité. Pour ceux qui connaissent déjà l’artiste, rassurez-vous, vous pourrez admirer l’une de ses œuvres phares, à savoir ses Terracotta Daughters. Si l’œuvre intégrale, composée de 108 sculptures en terre cuite, a

françaises. Prune Nourry c’est d’ailleurs la plus jeune artiste qui ait jamais exposé dans l’illustre musée Guimet. Du haut de ses 32 ans, l’artiste nous livre une réflexion des plus touchantes et pertinentes sur l’avenir de l’humanité. Pour ceux qui connaissent déjà l’artiste, rassurez-vous, vous pourrez admirer l’une de ses œuvres phares, à savoir ses Terracotta Daughters. Si l’œuvre intégrale, composée de 108 sculptures en terre cuite, a été ensevelie dans un lieu secret en Chine. Ici, on pourra admirer leurs huit originaux, et autant vous dire que l’émotion est ici à son comble face à ses collégiennes grandeur nature, une référence aux soldats du premier empereur, dans une version féminine qui nous rappelle les drames de la politique chinoise de l’enfant unique, et les fantômes des centaines de millions de filles qui ne verront jamais le jour.

été ensevelie dans un lieu secret en Chine. Ici, on pourra admirer leurs huit originaux, et autant vous dire que l’émotion est ici à son comble face à ses collégiennes grandeur nature, une référence aux soldats du premier empereur, dans une version féminine qui nous rappelle les drames de la politique chinoise de l’enfant unique, et les fantômes des centaines de millions de filles qui ne verront jamais le jour.![IMG_0297[1].JPG](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_02971.jpg?w=648) mais l’artiste nous chahute volontairement, pour souligner le paradoxe qui existe en Inde, entre la femme, source de fécondité peu considérée, et l’animal sacré, symbole de fertilité, vénéré. Une manière de dénoncer le paradoxe qu’il y a à sacraliser la vache au détriment d’une petite fille, appelée à devenir mère un jour.

mais l’artiste nous chahute volontairement, pour souligner le paradoxe qui existe en Inde, entre la femme, source de fécondité peu considérée, et l’animal sacré, symbole de fertilité, vénéré. Une manière de dénoncer le paradoxe qu’il y a à sacraliser la vache au détriment d’une petite fille, appelée à devenir mère un jour. installant une tête de bouddha colossale, de plus de 3 mètres de haut, plantée de milliers de bâtons d’encens, comme autant d’aiguilles réparatrices. Un Bouddha monumental qui fait office de fil rouge tout au long de l’exposition pour aider le visiteur à comprendre l’histoire des civilisations asiatiques. Et ce Bouddha déborde de toutes parts et s’installe à chaque étage du musée, en référence à celui détruit en 2001 par les Talibans, un colosse de près de 40 mètres. On découvrira ainsi au 1erétage sa main monumentale, de près de 5 mètres de haut, on ses pieds au rez-de-chaussée, dans des dimensions absolument vertigineuses.

installant une tête de bouddha colossale, de plus de 3 mètres de haut, plantée de milliers de bâtons d’encens, comme autant d’aiguilles réparatrices. Un Bouddha monumental qui fait office de fil rouge tout au long de l’exposition pour aider le visiteur à comprendre l’histoire des civilisations asiatiques. Et ce Bouddha déborde de toutes parts et s’installe à chaque étage du musée, en référence à celui détruit en 2001 par les Talibans, un colosse de près de 40 mètres. On découvrira ainsi au 1erétage sa main monumentale, de près de 5 mètres de haut, on ses pieds au rez-de-chaussée, dans des dimensions absolument vertigineuses.![IMG_0502[1]](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_05021.jpg?w=225&h=300) bouddhique, le bouddhisme tantrique et, pour une moindre part, l’hindouisme et le jainisme. Pour cette occasion le musée Guimet a choisi d’interroger ses propres

bouddhique, le bouddhisme tantrique et, pour une moindre part, l’hindouisme et le jainisme. Pour cette occasion le musée Guimet a choisi d’interroger ses propres ![IMG_0531[1]](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_05311.jpg?w=168&h=224) collections, dont certaines, ressorties des réserves, restaurées ou nouvellement acquises forment un ensemble de 113 chefs-d’œuvre. C’est avec un regard d’orfèvre que le musée explore et pose ainsi le cadre des échanges du métal inaltérable et des raisons de sa rareté, qu’il soit poudre d’or au Japon, en Chine ou en Corée, émissions monétaires dans l’Afghanistan kouchane ou parure de maharajahs indiens. Les techniques d’extraction et du travail de l’or sont abordées en préambule, avant qu’un florilège de splendeurs ne raconte sa fabuleuse épopée, les raisons de l’attrait et du pouvoir de séduction qu’il suscita en Asie, mille et une histoires en or.

collections, dont certaines, ressorties des réserves, restaurées ou nouvellement acquises forment un ensemble de 113 chefs-d’œuvre. C’est avec un regard d’orfèvre que le musée explore et pose ainsi le cadre des échanges du métal inaltérable et des raisons de sa rareté, qu’il soit poudre d’or au Japon, en Chine ou en Corée, émissions monétaires dans l’Afghanistan kouchane ou parure de maharajahs indiens. Les techniques d’extraction et du travail de l’or sont abordées en préambule, avant qu’un florilège de splendeurs ne raconte sa fabuleuse épopée, les raisons de l’attrait et du pouvoir de séduction qu’il suscita en Asie, mille et une histoires en or.![IMG_0552[1].JPG](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_05521.jpg?w=4032) symboliques : comment la lumineuse carnation du Bouddha ne pourrait être mieux évoquée que par l’or ? Vecteur d’éternité, l’or tient dans la parure funéraire, comme dans la conservation de la mémoire, une fonction de premier ordre, offrant à la statuaire de saisir de façon frappante ces facteurs d’unité à l’échelle du continent asiatique, de telle sorte que lorsque l’or est absent, le bronze ou le bois doré en jouent les substituts.

symboliques : comment la lumineuse carnation du Bouddha ne pourrait être mieux évoquée que par l’or ? Vecteur d’éternité, l’or tient dans la parure funéraire, comme dans la conservation de la mémoire, une fonction de premier ordre, offrant à la statuaire de saisir de façon frappante ces facteurs d’unité à l’échelle du continent asiatique, de telle sorte que lorsque l’or est absent, le bronze ou le bois doré en jouent les substituts.![IMG_0558[1].JPG](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_05581.jpg?w=4032) dernier bastion de l’Inde moghole. Promesse d’éternité, l’or défie le temps humain et joue la transmission : l’empereur de Chine, Qianlong, avec ses calligraphies à l’encre d’or des plaques de jade, ses propres écrits sur l’éthique et la philosophie en politique, à l’occasion de son quatre-vingtième anniversaire. Investi de la symbolique du pouvoir et de la richesse, l’or et ses fastes sont évoqués à travers le matériel archéologique mais aussi la production d’objets de luxe dans l’Inde moghole. En Afghanistan, durant la dynastie kouchane (1er-3e siècle), le monnayage en or apparaît et la monnaie d’or qui fait référence à l’irruption des nomades dans le monde sédentaire, exprimait aussi l’immense prestige et la puissance du souverain, l’Altaï étant la source de l’or. En écho au monde des steppes, certains objets archéologiques tel que la couronne typique du royaume de Silla (5e-6e siècle) provenant d’une tombe de Kyongung en Corée, attestait de l’importance du faste au temps des Trois Royaumes.

dernier bastion de l’Inde moghole. Promesse d’éternité, l’or défie le temps humain et joue la transmission : l’empereur de Chine, Qianlong, avec ses calligraphies à l’encre d’or des plaques de jade, ses propres écrits sur l’éthique et la philosophie en politique, à l’occasion de son quatre-vingtième anniversaire. Investi de la symbolique du pouvoir et de la richesse, l’or et ses fastes sont évoqués à travers le matériel archéologique mais aussi la production d’objets de luxe dans l’Inde moghole. En Afghanistan, durant la dynastie kouchane (1er-3e siècle), le monnayage en or apparaît et la monnaie d’or qui fait référence à l’irruption des nomades dans le monde sédentaire, exprimait aussi l’immense prestige et la puissance du souverain, l’Altaï étant la source de l’or. En écho au monde des steppes, certains objets archéologiques tel que la couronne typique du royaume de Silla (5e-6e siècle) provenant d’une tombe de Kyongung en Corée, attestait de l’importance du faste au temps des Trois Royaumes. ![IMG_0563[1]](https://ledodosouslefilao.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/img_05631.jpg?w=648) Au Japon, l’or habille de grâce les éblouissants objets de laque, les paravents et textiles de l’apogée bourgeoise, les plus raffinés comme les plus frivoles du monde flottant, rappelant ici que la fascination pour le métal magique n’empêche pas le vieil adage : « tout ce qui brille n’est pas d’or ».

Au Japon, l’or habille de grâce les éblouissants objets de laque, les paravents et textiles de l’apogée bourgeoise, les plus raffinés comme les plus frivoles du monde flottant, rappelant ici que la fascination pour le métal magique n’empêche pas le vieil adage : « tout ce qui brille n’est pas d’or ». impressionnistes qui exaltent le passage des saisons et les lieux célèbres du Japon, visions urbaines et descriptions d’itinéraires poétiques au début de l’époque Edo, ou encore scènes de genre et intimistes dans l’art des grands maîtres Hokusai et Hiroshige qui ont su renouveler l’art de l’Ukiyo-e, cette exposition méditation présentera aussi des estampes nouvellement acquises de la période moderne, dont celles très graphiques d’Hasui Kawase. Véritable palette documentaire toute en finesse et aux subtiles couleurs, les estampes présentées couvriront une période de trois siècles et montreront la réalité d’une géographie et de ses territoires. Une ode à la dimension divine du spectacle de la nature dans le respect d’une harmonie fondamentale entre ses éléments et celle de l’être humain, où comment le rêve et le réel appartiennent à une même vision. L’exposition interroge la notion de paysage dans l’estampe et la considère dans un contexte plus général, celui de l’itinérance et de la fascination pour la ville, telle que celle-ci se développera et se perpétuera durant le 19e siècle. Avec l’idée d’une déambulation poétique, d’une gravitation autour d’une cité, qui introduit la notion philosophique du temps qui passe, c’est une présentation autant spatiale que temporaire qui en sera le propos naturaliste.

impressionnistes qui exaltent le passage des saisons et les lieux célèbres du Japon, visions urbaines et descriptions d’itinéraires poétiques au début de l’époque Edo, ou encore scènes de genre et intimistes dans l’art des grands maîtres Hokusai et Hiroshige qui ont su renouveler l’art de l’Ukiyo-e, cette exposition méditation présentera aussi des estampes nouvellement acquises de la période moderne, dont celles très graphiques d’Hasui Kawase. Véritable palette documentaire toute en finesse et aux subtiles couleurs, les estampes présentées couvriront une période de trois siècles et montreront la réalité d’une géographie et de ses territoires. Une ode à la dimension divine du spectacle de la nature dans le respect d’une harmonie fondamentale entre ses éléments et celle de l’être humain, où comment le rêve et le réel appartiennent à une même vision. L’exposition interroge la notion de paysage dans l’estampe et la considère dans un contexte plus général, celui de l’itinérance et de la fascination pour la ville, telle que celle-ci se développera et se perpétuera durant le 19e siècle. Avec l’idée d’une déambulation poétique, d’une gravitation autour d’une cité, qui introduit la notion philosophique du temps qui passe, c’est une présentation autant spatiale que temporaire qui en sera le propos naturaliste. sont importées par l’Archipel, pour la cérémonie du thé, que les Japonais ont transformée en un art de vivre à forte dimension cultuelle. C’est dans cette filiation que s’inscrit le collectionnisme d’Hikonobu Ise, porté notamment par son admiration pour la culture lettrée chinoise. Il raconte ainsi que chaque semaine, il sort de son étui l’un de ces objets, pour le contempler en dégustant un thé ; le sentiment de joie qu’il en ressent alors est au-delà du simple moment de détente. Ses choix semblent en effet guidés en premier lieu par l’émotion procurée par des objets qui « ont attrapé [son] cœur » et par le dialogue esthétique qui s’instaure avec l’œuvre dès le « premier regard » : face à une céramique Ming, représentant un combat de coqs, il fut ainsi « totalement ébloui et [se sentit] presque en état d’ébriété pendant les six mois qui ont suivi ». Le respect du Beau et la nécessité de réaliser des emballages propres à protéger les objets précieux, notamment des dangers sismiques, ont permis de conserver de manière exceptionnelle ces céramiques, dont les vibrants reflets des glaçures, les couleurs chatoyantes des émaux, les subtilités des décors sont d’une telle qualité que ces œuvres de plusieurs siècles semblent être à peine sorties du four. Présenter cette collection, c’est ainsi convier chacun à un voyage sensoriel et esthétique, dans l’intimité d’un passionné.

sont importées par l’Archipel, pour la cérémonie du thé, que les Japonais ont transformée en un art de vivre à forte dimension cultuelle. C’est dans cette filiation que s’inscrit le collectionnisme d’Hikonobu Ise, porté notamment par son admiration pour la culture lettrée chinoise. Il raconte ainsi que chaque semaine, il sort de son étui l’un de ces objets, pour le contempler en dégustant un thé ; le sentiment de joie qu’il en ressent alors est au-delà du simple moment de détente. Ses choix semblent en effet guidés en premier lieu par l’émotion procurée par des objets qui « ont attrapé [son] cœur » et par le dialogue esthétique qui s’instaure avec l’œuvre dès le « premier regard » : face à une céramique Ming, représentant un combat de coqs, il fut ainsi « totalement ébloui et [se sentit] presque en état d’ébriété pendant les six mois qui ont suivi ». Le respect du Beau et la nécessité de réaliser des emballages propres à protéger les objets précieux, notamment des dangers sismiques, ont permis de conserver de manière exceptionnelle ces céramiques, dont les vibrants reflets des glaçures, les couleurs chatoyantes des émaux, les subtilités des décors sont d’une telle qualité que ces œuvres de plusieurs siècles semblent être à peine sorties du four. Présenter cette collection, c’est ainsi convier chacun à un voyage sensoriel et esthétique, dans l’intimité d’un passionné.

the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. He was the Charles and Marie Robertson Professor of International Affairs at Princeton University.

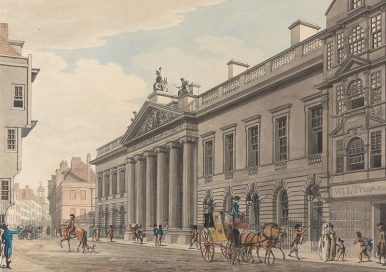

the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. He was the Charles and Marie Robertson Professor of International Affairs at Princeton University. The rise, consolidation, and fall of the British Raj is a fascinating story that inevitably raises passions throughout the Indian subcontinent and in Britain itself. What was the nature of the Raj? Was it a pre-planned, colonial enterprise? Did it have some positive aspects? How did it come about anyhow, and how was it ruled?

The rise, consolidation, and fall of the British Raj is a fascinating story that inevitably raises passions throughout the Indian subcontinent and in Britain itself. What was the nature of the Raj? Was it a pre-planned, colonial enterprise? Did it have some positive aspects? How did it come about anyhow, and how was it ruled? Akhilesh Pillalamarri is an international relations analyst, editor, and writer. He was previously an assistant editor at The National Interest and editorial assistant at The Diplomat. He received his Master of Arts in Security Studies from the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, where he concentrated in international security. He mainly writes on South Asia, Central Asia, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and East Asia.

Akhilesh Pillalamarri is an international relations analyst, editor, and writer. He was previously an assistant editor at The National Interest and editorial assistant at The Diplomat. He received his Master of Arts in Security Studies from the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, where he concentrated in international security. He mainly writes on South Asia, Central Asia, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and East Asia.

Valley. He is former Vice-President at Forrester Research, a leading US-based technology research and consulting firm. At Forrester, he investigated how globalised innovation – with the rise of India and China as both a source and market for innovations – is driving new market structures and organizational models called « Global Innovation Networks ». During his tenure at Forrester, he advised senior executives around the world on technology-enabled best practices to drive collaborative innovation, global supply chain integration, and proactive customer service. He served as the Executive Director of the Centre for India & Global Business at Judge Business School, University of Cambridge, where Jaideep Prabhu was the director.

Valley. He is former Vice-President at Forrester Research, a leading US-based technology research and consulting firm. At Forrester, he investigated how globalised innovation – with the rise of India and China as both a source and market for innovations – is driving new market structures and organizational models called « Global Innovation Networks ». During his tenure at Forrester, he advised senior executives around the world on technology-enabled best practices to drive collaborative innovation, global supply chain integration, and proactive customer service. He served as the Executive Director of the Centre for India & Global Business at Judge Business School, University of Cambridge, where Jaideep Prabhu was the director.